Perspectives on Mountain Lions and Mankind

Severed heads of 11 mountain lions among 24 killed by Animal Damage Control on December 1988-May 1989 in the Coronado National Forest, Galiuro Mountains, Arizona. These lions were killed to protect livestock grazing on public, not private land.

Download the printable version

The mountain lion, also commonly known as the cougar or puma, is the great cat of the Americas. To scientists, he is puma concolor – the cat of one color. To those who are of a more romantic mindset, he is the “ghost cat” or the “spirit of the mountains.” To Native Americans he has always been a sacred being – an animal of mystery and power. Sadly, to contemporary wildlife managers, he is merely a game animal, a trophy, and often, a perceived legal liability and an inconvenience.

On September 24, 2009 I was honored to participate in a series of events held at Fort Lewis College in Durango, Colorado designed to educate the community and campus about mountain lions.

Within the past year or so, several mountain lions had entered the Durango city limits where they were deemed to be a threat to public safety and were killed by the Colorado Division of Wildlife. The interest generated in these incidents led Fort Lewis College to choose David Baron’s The Beast in the Garden (2003) – a book that documents a fatal cougar attack – as its Freshmen Reader for their “Common Reading Experience” program. In addition to having their freshmen read The Beast in the Garden, Fort Lewis College also organized other educational events including several lectures and classroom presentations, an evening panel discussion, and a truly first-rate museum exhibit entitled “Mountain Lion!” at their Center for Southwest Studies. This comprehensive exhibit will run until the fall of 2010 and is a “must see” for anyone interested in the big cat.

I was invited to make several contributions to the mountain lion program. I started the day by doing a one hour interview on the campus radio station with Dr. Bridget Irish – organizer of the lion program, and Dr. Rick Wheelock – a longtime friend and colleague who teaches Native American studies at Fort Lewis College. The focus of this interview was the role of mountain lions in Native American culture. After that, I visited Dr. Irish’s freshman class where I answered questions regarding a chapter I had written for the book Listening to Cougar (2007) edited by Marc Bekoff and Cara Blessley Lowe. This chapter – “The Sacred Cat: The Role of Mountain Lion in Navajo Culture and Lifeway” – had been one of the assigned readings for the students. Later in the day I also had the opportunity to speak to two of Dr. Wheelock’s Native American studies classes, and to view the museum exhibit.

The featured event of the awareness program was the evening panel – entitled “Living with the Beast: Perspectives on Mountain Lions and People” – for which I served as one of four participants along with the moderator, the before mentioned author Dave Baron. I was amazed when I took the stage for this two hour event – every seat in the house was full and many people were standing alongside the aisles. I was later told that the auditorium seated 600 people. Clearly, mountain lions were very much on the minds of the people of Durango and the students of Fort Lewis College.

My fellow panelists were Patricia Dorsey, the area Wildlife Manager for the Colorado Division of Wildlife, Dr. Lee Ann Harbison, a biologist, rancher, and mother, and Ed Zink who is also a Durango-area rancher and hunter. Mr. Zink came onto the panel as a replacement for Dr. Marc Bekoff who cancelled the evening before. I was extremely disappointed that Bekoff, a professor emeritus of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of Colorado, and perhaps the foremost ethologist (one who studies the emotional and behavioral lives of animals) in the country, could not attend. I have read many of his books, and over the past couple of years and had also corresponded with him. Consequently I had been most anxious to meet him. More importantly, this put me in the situation of being “the odd man out” on this panel. I think that Marc and I would have approached lion issues from pretty much the same position. While I will not label the other three panelists as necessarily being “anti-lion,” their perspectives were all very similar to each other, and far different than my own. In sum, they approached things from a purely anthropocentric viewpoint, whereas my own views were far more “lion-centric.” Fortunately throughout the evening Mr. Baron – perhaps recognizing that I was somewhat outnumbered – allowed me adequate time to express my opinions and respond to most of the statements made by the other panelists.

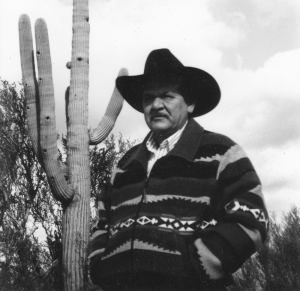

My own background and experience dealing with mountain lion issues goes beyond the Native American component. While living in Arizona I participated in several mountain lion track count surveys and was able to associate with some of the best cougar biologists in the country, most notably Harley Shaw, who I worked with for many years on a mountain lion and bear track count in the Huachuca Mountains. I was also a wildlife activist who volunteered and/or provided assistance to a number of conservation groups working on large carnivore issues – the Defenders of Wildlife, Sierra Club, The Center for Biological Diversity, Sky Island Alliance, and the Animal Defense League of Arizona. Often my efforts with these organizations focused on lion issues. On several occasions I wrote position papers and testified at various hearings against what I believe to be the archaic predator control policies of the Arizona Department of Game and Fish (AGFD) – an agency that largely represents the interests of hunters and the ranching community. In 2001, for example, I became involved when AGFD announced their intent to kill up to 36 lions as part of their plan to reintroduce desert bighorn sheep into a mountain range for the sole purpose of providing hunters with trophies. In 2004, I took a very active role in opposing AGFD when they initiated a plan to kill four lions that they deemed to be a threat to public safety in Sabino Canyon on the outskirts of Tucson – despite the fact that these lions had demonstrated no aggressive behavior. Then in 2006, I again spoke out against plans by U.S. Fish and Wildlife to allow AGFD to open a hunting season on lions on the Kofa Wildlife Refuge, once again for the purpose of reducing predation on bighorn sheep. I will talk about each of these events throughout this essay and at the end I have provided a link to the position papers I wrote on each.

Before discussing my comments on the panel, I should probably say something about our moderator, David Baron, and his book, The Beast in the Garden.

The Beast in the Garden provides a thorough and very graphic account of the killing of an eighteen-year old high school athlete named Scott Lancaster by a mountain lion in Idaho Springs, Colorado on January 24, 1991. Baron’s thesis is a simple one amidst a complex issue, namely that local nature loving people – especially in the nearby city of Boulder – purposefully created a paradise (the “Garden”) for deer and other prey animals at the rural-urban interface, which in turn attracted mountain lions (the “Beast”). He argues that this close proximity to humans created habituated mountain lions that lost their fear of humans and posed an obvious threat to public safety. He further argues that the liberal attitudes of the area – which included an aversion to killing lions – created a scenario which tied the hands of local wildlife and law enforcement people, thus making the Lancaster tragedy inevitable. Baron provides a detailed account of the events leading up to the death of Lancaster and documents the efforts of those who attempted unsuccessfully tried to raise the alarm. The Beast in the Garden proved popular but controversial in some quarters. The vast majority of reviews were favorable. Others, most notably by Wendy J. Keefover Ring, Director of the Carnivore Protection Program, and Ken Logan – one of the nation’s leading lion biologists – were not. The impact of The Beast in the Garden is undeniable. In some ways this book was the Jaws of its time period, instilling in some people fear – or more likely reinforcing a pre-existing media-driven fear – of lions, and reinforcing the belief that we need to kill more cougars to make the world safer for humans. AGFD, for example, used The Beast in the Garden in its propaganda campaign to justify their killing of the cougars in Sabino Canyon and elsewhere.

I first read The Beast in the Garden when it was initially released. I received it as a Christmas present and read the entire book that day. I found this book so compelling that I could not set it down. Baron is an outstanding writer and the story he weaves is a gripping one. While I do not agree with his before mentioned basic premises, and while there were specific items that I had particular problems with – for example his acceptance of a ridiculous theory proposed by a genetic scholar at the University of Arizona that Native Americans drove Pleistocene mountain lions into extinction – I thoroughly enjoyed this book and would highly recommend it. Anyone reading this book, however, should accept the fact that Baron is a journalist. He writes for a popular audience and he writes to sell books. He employs a descriptive style of prose that some may think is “over the top.” His graphic description of Scott Lancaster’s body after he was killed reads like a script from the TV crime drama CSI, and some lion advocates have deemed his language to be needlessly inflammatory. But the fact is that death by a lion is a brutal affair and the power and potential deadliness of this perfect predator should be appreciated. And while Baron is not a lion expert and some may rightfully question some of his assumptions and conclusions, The Beast in the Garden is a very well researched and evenly presented work.

The panel covered a lot of ground and it is impossible in this essay to go over everything that we discussed, and often debated. Consequently, I will only focus this paper on five points that I made and wish to elaborate on. I will also restrict this essay largely to the main conservation issues of the cougar debate, rather than to the Native American components of my remarks. My comments in regard to Native American views about cougars are basically the same as what I have written about jaguars and the Macho B tragedy found elsewhere on this blog.

With that background, here are the following major points that I made during the panel discussion “Living with the Beast:”

1. There is no proof or evidence that mountain lion populations are increasing in the western United States.

This is the great “urban legend” of modern day mountain lion conservation and management.

Baron’s opening question to our panel was directed at Patricia Dorsey, a Wildlife Manager for Colorado Division of Wildlife. He asked her a simple question: “How many mountain lions are there in Colorado?” Dorsey’s reply: “We don’t know how many mountain lions we have, but we know we have more than ever before.” Her response was typical of people working in the wildlife management field. One of the great myths being perpetuated by state wildlife agencies throughout the country is that cougar populations are exploding out of control. Admittedly human-cougar encounters have increased, and cougars are being sighted in places where they have not been seen in years, such as in the Midwest. But this is not necessarily evidence, and certainly not proof, of increasing cougar populations.

Mountain lions tend to be secretive, cryptic animals that in most cases avoid humans. They generally live in the most rugged and inaccessible habitat imaginable. It is impossible to estimate cougar populations. At best, wildlife agencies can only make extremely rough estimates of the number of the big cats that live within the boundaries of their states.

Increased cougar sightings, and increased cougar- human contact are a direct result of human encroachment into mountain lion territory – a reality that at least one of my fellow panelists, Mr. Zink, vehemently disagreed with. Humans are invading and taking over cougar habitat at an unprecedented pace. We are building our homes, ranches, and recreational retreats in cougar country. In addition there are more hikers, backpackers, skiers, and people on ATVs and snowmobiles in the backcountry than ever before. Every piece of land that is cleared for a new housing development or shopping mall, every highway or recreational back road created, is cougar habitat lost. The big cats are simply running out of real estate and have to go somewhere, and everywhere they are pushed to, they encounter humans. Consequently, mountain lions are finding themselves increasingly coming into contact – and conflict – with humans, a species which most have no prior experience with.

Biologists generally recognize three classes within a cougar population: resident male and females, transient male and females, and dependent offspring – the kittens of resident females. Resident adults tend to be mature permanent residents living within a home range – a geographical area of land that could be up to 500 square miles in size. Although cougars are generally solitary, kittens stay with their mothers until they are almost two years old. They then generally disperse – especially the males who are no longer tolerated by the dominant resident male – to become transients. It is largely the transients that humans are seeing and encountering. A shrinking land base means less country for young lions to establish new home ranges.

2. Mountain lions that enter into urban areas do not necessarily pose a threat and do not necessarily have to be killed.

Mountain lions are not inherently dangerous, and in the vast majority of cases in which they enter into urban settings do not pose a threat to humans. This remains true even in cases of actual contact with humans. Cougar attacks are almost unheard of. Over the past 100 years there have been a total of 14 humans killed in the entire United States and Canada by mountain lions. This is less than two people per year despite tens of thousands of actual mountain lion-human encounters.

In contrast during this same time period 15,000 people have been killed by lightning, 10,000 by deer (mostly in deer-vehicle collisions), and 4,000 by bees. Every year in the United States on average, 43,000 people die in automobile accidents, 24,000 die from accidental poisoning, 17,000 from accidental falls – mostly at home, and 3000 drown. In an average year in the United States over 700 people die in bicycle accidents, 20 are killed in domestic dog attacks, 20 by hunting accidents, 11 due to snake bites and allergic reaction to the anti-venom used in the treatment of snake bites, and believe it or not – as our moderator Dave Baron pointed out – an average of 3 people are killed each year by escalators, and 2 more each year by having vending machines fall on them. In sum, the comparative chance of being killed by a mountain lion is astronomically slim.

Mountain lions that enter into urban areas are not out hunting humans, they are hunting space. They want only to be left alone. Most of these animals are simply transients on the move that “wander” into cities. If left alone, they generally will wander out.

In the case of the before mentioned Sabino lions, the Aspen forest fire, the worst in the history of the Santa Catalina Mountains, had pushed wildlife down into the Tucson Basin. At the time I was living in Tucson and hiked Sabino Canyon close to 80 times a year. On most days I would see two or three deer. Soon after the fire I began to see perhaps as many as twenty. With the deer, I knew would come the lions. I wrote a letter to AGFD bringing up this issue, and they never responded. Soon afterwards hikers began to report encounters with cougars that “came too close” or “showed no fear.” In comments that made the front page of the newspaper, Larry Raley, the head ranger of the Santa Catalina Rancher District, shrilly proclaimed “that an attack was eminent” and closed the park. AGFD announced their intent to go in and kill all of the lions.

I should add here that Sabino is not truly an “urban” setting but rather a natural area in which cougars belonged. Barely one mile into the park and the land is officially designated as “wilderness.” The houses that have sprung up along the borders of Sabino have encroached on mountain lion habitat. The vast majority of the people who live in this area love and understand nature and spoke out against the removal of the lions. Others – those few who desire a safe and sanitized natural world – wanted the lions dead or removed. AGFD – in what can only be deemed “propaganda” – made much of the fact that there was an elementary school in this area and that the cougars posed a threat to the children. At one point several people were reported in the newspaper as having seen a cougar on school grounds. Defenders of Wildlife asked me to investigate this alleged sighting. I searched the area completely around the school and found no cougar tracks despite having excellent terrain to track. I also located one of the three people who had reported seeing the “cougar” on the school grounds and this woman, who was very familiar with the wildlife of Sabino and who often saw bobcats on her own property. She emphatically told me that the animal she saw and reported to AGFD was actually a bobcat, not a mountain lion. Her two companions, who had never seen either a bobcat or a cougar in their lives, told AGFD that it was a mountain lion. AGFD chose to believe her two companions.

The only thing that AGFD seems to have had right during this tragic series of events was the correct number of cougars that had come down into Sabino, four. I went into Sabino and found the tracks of four different cougars: One set of tracks I assumed belonged to a very large male (Some trackers claim they can distinguish between male and female cougars, I can’t). Three other set of tracks were considerably smaller and I assumed this might be a female and her two nearly grown kittens. It was later it was proven that all three of these smaller tracks belonged to cats that were approximately two years or younger.

I found by tracking the big male that he kept to himself and completely avoided people. He obviously knew that humans meant trouble. It was the younger cougars that were being seen by people. Contrary to what every wildlife agency wants people to believe, wild animals, including cougars, do not possess an inherent fear of humans. Fear is a learned emotion. All cats are curious and cougars are no exception. Mountain lions are well known for following people for no other reason than to simply observe them. Younger cats are especially curious. Certainly these adolescent cougars had no prior experience with – and consequently no reason to fear people. In my estimation the Sabino lions were guilty of no more than being curious young animals. At the peak of the controversy AGFD released a descriptive list of sightings and encounters that had occurred as a means of justifying their actions. Paul Beier, a professor of wildlife biology at Northern Arizona University, and a mountain lion specialist who had made extensive studies of cougar attacks on people, reviewed the list and determined that the lions were not acting unusual and posed no apparent danger to people. Public sentiment also leaned heavily in favor of the cougars. 85% of the letters to the editor of the Arizona Daily Star newspaper and letters sent to AGFD were critical of plans to kill or even remove the cougars from Sabino. Governor Janet Napolitano and several elected state representatives also intervened, calling for AGFD to call off their hunt and seek other solutions. Despite the public and political opposition, AGFD carried out their plans, setting out snares and also bringing in a professional lion hunter with hounds. In the end they trapped one young female near a deer she had killed. This female was taken to the Southwest Wildlife Rehabilitation Center in Scottsdale to live out the rest of her life in captivity. AGFD would later kill the two other young females and estimated their ages to be less than two years of age. Again, these lions did nothing wrong other than approaching hikers on the trail. Neither showed any aggressive behavior, yet both were still shot and killed by AGFD officers. The big male fortunately escaped their best efforts to hunt him down.

The case of the Sabino lions stands as a classic case of a state wildlife agency over-reacting due to fear and ignorance. Government agencies like AGFD are always fearful of being sued for failing to protect people from the hazards – and perceived hazards – of the outdoors. In 1996 a bear had mauled a camper named Anna L. Knochel in the Santa Catalina Mountains. Earlier this bear had been deemed a nuisance to other campers and had been captured and relocated by AGFD only to return. AGFD was sued by the girl’s family who were awarded a $2.5 million settlement. After this landmark court decision it became standard operating procedure for AGFD – and undoubtedly many other state wildlife agencies throughout the nation – to kill, not relocate, bears and lions that came into contact with people. My own research into AGFD and its handling of “nuisance” black bears, revealed that prior to the Knochel case the department relocated approximately 85% of such bears, whereas after the Knochel case, they euthanized approximately 85%.

I understand that a mountain lion entering into an actual populated urban area does indeed pose a potential – though still remote – threat to humans. No one wants a lion attack and a human mauling or death. There is also the even greater likelihood that the animal itself will be harmed in terms of perhaps being injured or killed by an automobile, or being electrocuted by telephone transformers and wires. In some cases it might be possible to allow such cougars to leave on their own, or to “haze” them out of the area. In other cases it might be more practical for wildlife officials to physically remove and relocate the cougar themselves. If treed – which cougars in urban areas often are – this can be done in the same manner they are captured and radio-collared in the wild for research, through the use of a tranquilizer gun. Generally speaking, a treed cougar hit with a dart remains in the tree until the drugs have taken effect. If on the ground, capture guns – net guns – can be used. In extreme cases, perhaps in regard to a cougar wandering deep in a heavily populated urban setting and only if no other option available, the lethal removal of a cougar is justified.

In the case of the Sabino Canyon lions, an example of cougars moving into a natural area adjacent to human occupation, every option was open to AGFD, but they chose only to consider the lethal – the easy – option. In a personal letter to me, Harley Shaw expressed his option might hazing might work. Many others suggested this option but AGFD refused to even consider it stating that hazing “never worked.” The capture and relocation of the Sabino lions – the most obvious and workable solution – was also rejected by AGFD on the grounds that the relocated cougars would simply come in conflict with the resident cougars in the areas they were released. This excuse also was misleading and dishonest. To begin with, all of the Sabino Canyon cougars were females which generally are not as territorial as males. Also, AGFD keeps records of every cougar legally killed by hunters. Any captured cat could simply be released in an area in which the prior resident occupant had been “harvested.”

3. We need to learn more about mountain lion behavior.

The fact is that while we know almost everything about the natural history of mountain lions, we know almost nothing about mountain lion behavior.

Over the years numerous biologists – Maurice G. Hornocker, Harley Shaw, and Kenneth A. Logan and Linda L. Sweanor to name just a few – have studied and written extensively on the natural history of mountain lions. But most of this research has been very basic biology: preferred habitat and prey species, migration patterns, and reproductive information. Moreover, almost all of this research has been financed through and driven by state wildlife agencies. The goal of these agencies is to manage mountain lions as a game animal for hunting, or to manage the impact of cougars on other preferred hunting species like deer, elk, and bighorn sheep, or to protect livestock. In other words, most cougar research is designed to learn more about them in order to more effectively kill them, but not really understand them.

Wildlife mangers generally mask their ignorance of cougar behavior by attributing everything to instinct. In sum, they tell us that mountain lions do what mountain lions do because they can’t help it. Some innate impulse triggered by a given stimulus drives them to action.

The very concept and popular use of the term instinct – which I see as being only the initial “call to action” – has all but out lived its usefulness in attempting to understand animal behavior, and certainly tells us nothing about mountain lion behavior specifically. It is quite obvious that cougar behavior – in fact, almost all animal behavior – is more a product of conscious thought processes. A mountain lion stalking a deer for example is a thinking creature whose mind is translating multiple scenarios and outcomes: “Which deer in this herd should I focus my attention to?” “What is the best approach to reaching this deer?” “What are the chances of me catching this deer?” “Might I injure myself in the process?” While a cougar may not be thinking these things in human terms, he is most certainly thinking.

In recent years the field of cognitive ethology has risen to prominence. As noted earlier, cognitive ethology is the study of the emotional, and consequently the behavioral lives of animals. It starts with the premise that every animal is an intelligent individual, and that animal behavior is largely the product of two separate but related processes: thought and emotions. In sum, cognitive ethologists believe that animals possess conscious rational thought processes – not simply “instinct” – as advocated by most scientists. This thought process includes a degree of self-awareness on the part of the animal. Cognitive ethologists also generally believe that animals are sentient, that they are capable of experiencing a wide range of emotions that are in many ways comparable to those enjoyed by humans: love, hate, fear, joy, sadness, jealousy, and empathy to name a few.

Cognitive ethology represents the “brave new world” of wildlife studies. Yet most wildlife managers continue to deny that animals possess either rational thought or emotions. They accuse those who think otherwise of engaging in “anthropomorphism” – of attributing human qualities to animals. Perhaps this is not a bad thing. Perhaps it is time that we begin to view – and study – animals in a different way. As it stands now, much of what passes for wildlife “research” is little more than an exercise in repetition and redundancy. In reality, we have learned little that is new, and almost nothing of importance, about cougars in recent decades. How much more can one learn a radio-collared lion?

4. We need to re-evaluate and change the way we manage mountain lions … and people.

Historically, mountain lions and other predators were killed on sight by the early Euro-American settlers. With the advent of large scale cattle ranching in the American west during the 1880s, predator control was carried out with a passion that bordered on near-religious zealotry. The federal government’s Predatory Animal and Rodent Control agency (PARC) led this war of extermination with guns, traps, and poisons, and by the 1930s grizzly bears and wolves were all but extirpated throughout most of their range. Mountain lions escaped a similar fate only because they tended to inhabit the more rugged and remote mountainous areas. PARC eventually morphed into Department of Agriculture-based agency named Animal Damage Control (ADC). With a desire to appear more politically correct, ADC recently changed its name to “Wildlife Services.” This organization – one of the most secretive agencies in the United States government with an annual budget of more than $100 million – $30 million of which is actually devoted to lethal animal control – killed nearly 3 ½ million animals in 2009. Although their “stock in trade” is coyotes – about 90,000 every year – Wildlife Services also kills approximately 340 cougars annually.

Wildlife officials commonly state that they manage mountain lions using “the best science available.” Nothing can be further from the truth. In reality, politics, not science, drives mountain lion management, and western state wildlife managers serve two masters: hunters and livestock ranchers.

Wildlife management is a numbers game and wildlife managers are trained to think in terms of populations. In order to maintain an adequate number of deer, elk, bighorn sheep, or other ungulates to satisfy the desires of hunters, rules and regulations are established to make this possible. For example, hunting seasons and bag limits are set. Also, the hunting of ungulates is also banned during the spring when the females are giving birth to, or are accompanied by their young. These rules are established to maintain a healthy “breeding stock” to insure a maximum “carrying capacity” – the maximum number of animals a particular geographic area can sustain. The ultimate goal is to provide a maximum number of targets for future hunting. Mountain lions enter into the equation because they eat ungulates and are the “X” factor – the factor that cannot be controlled.

Mountain lions are now classified as a big game species in almost every state and are managed accordingly with set hunting seasons and bag limits. The main exceptions are Texas and California. In Texas, although cougars are classified as being a big game species, the state treats the big cat as “vermin” and allows them to be killed whenever and wherever they are encountered with very few restrictions. In California, it is the opposite, mountain lions are protected. In 1990 the state passed Proposition 117 – a citizen’s initiative which banned the sport hunting of cougars.

Hunters generally support mountain lion and other predator control. They view mountain lions as being competitors and wrongly believe that reducing the number of cougars will result in a corresponding increase in ungulate populations. Most hunters who kill a cougar believe that they are doing both the ungulates and themselves a favor. State wildlife agencies also accept this false logic and encourage the hunting of cougars, or in some cases, carry out their own aggressive cougar “control” programs. A good example of this was an AGFD program I mentioned earlier. In 2001, AGFD – in what they labeled a “scientific experiment” – proposed killing up to 36 mountain lions – pretty much the entire population – in and near the Four Peaks Wilderness area. The purpose of this slaughter was to cleanse the area of predators in order to increase the survival rate for recently reintroduced desert bighorn sheep. AGFD – over the objections of numerous biologists, including its own, initiated the sheep reintroduction program in areas they admitted were “secondary sheep habitat,” in some cases where previous reintroduction attempts had failed, and even in areas – including the Four Peaks Wilderness – where sheep had never historically inhabited. They did so largely due to encouragement and financial support from the Arizona Desert Bighorn Sheep Society – a small yet very wealthy and politically influential organization of sheep hunters. When regular sport hunters were unable to kill enough lions, AGFD hired a professional lion hunter – a convicted felon who had recently lost his guide license for illegally killing 19 cougars – to do the job for them.

It is my opinion that the preemptive killing of mountain lions or any predator for the sole purpose of increasing game animals is unjustifiable and unethical. If an individual predator can be proven to be killing a disproportionate number of threatened or endangered animals – perhaps a lion killing within a certain population of bighorn sheep – and if no other alternative exists – then and only then I would support the killing of that individual lion.

State wildlife agencies also have to keep livestock ranchers happy as well. They do so in order to insure that these private land owners continue to keep open their ranchland to hunters. Mountain lions do occasionally kill livestock and are generally hated by ranchers. Most states issue depredation tags to ranchers that grant them permission to destroy specific lions that are killing livestock. In practice, however, ranchers – at least in Arizona – seldom apply for such tags and simply kill lions on sight. The “Old West” adage of “shoot, shovel, and shut up” comes into play and I strongly suspect that for every lion that is legally killed under a depredation tag, another 10 are taken and never reported. I know of one rancher in southeast Arizona who kills a number of cougars every year. State agencies tend to simply turn a blind eye to such events. The before-mentioned professional lion hunter who had been arrested for killing 19 cougars illegally in Arizona – only to be later employed by AGFD to kill more lions – had been initially hired and secretly paid by livestock ranchers.

In Texas, a “perfect storm” of special interests combine to create a situation where cougars, as one hunting website boasts, “may be legally taken in any number, by any method, 365 days a year!” In addition to responding to the usual clamor by hunters and cattle ranchers to kill mountain lions, Texas Game and Fish also work to protect the interest of land owners who engage in “deer ranching” – a multi-million dollar industry. 99% of deer hunting in Texas takes place on private ranches where deer inhabit large areas of land bordered by high fences where they are managed like livestock. In such facilities deer are genetically engineered and are fed vitamin enriched pellets throughout the year to assure maximum antler growth and body weight. They are then are baited and shot over stands by hunters who pay thousands of dollars to pick and choose the trophy they want. Success rates are better than 95%. This is not “sport hunting,” it is big business and clearly a cougar that can potentially kill and eat a $10,000 trophy buck is a liability risk that can not be tolerated.

Without question Texas and Arizona are the two states that have the greatest anti-predator bias and where mountain lion mismanagement is at its worst. The fact is, however, that most western state wildlife agencies hold similar views. As noted earlier, no state wildlife agency allows the hunting of any ungulate in the spring. Yet almost every state – including Washington State – allows the spring hunting of lions and bears. As a result, untold numbers of lion kittens and bear cubs are orphaned and left to die of starvation when their mothers are killed by spring hunters. The Cougar Foundation reports that the Washington Department of Game and Fish by its own admissions estimates that 26 lion kittens have been left orphaned by spring lion hunts over the past four years. This is undoubtedly a very, very conservative estimate.

It is my opinion that the spring hunting of any animal is never justified.

Mountain lions are mismanaged in other ways as well. As noted earlier, hunting seasons and bag limits are created on ungulates to maintain healthy populations of those animals. No wildlife agency talks about maintaining a carrying capacity of cougars and efforts are often made to kill as many as possible. In the before mentioned case of the Sabino lions AGFD never once considered the ramifications of removing three females from the Santa Catalina mountain range.

Increasingly, state wildlife agencies have come under scrutiny by the general public. Nowhere is this more evident than in the questioning of wildlife policies designed to manage predators, especially cougars. Mountain lions are charismatic animals that are widely popular with the general public. The majority of people – most of whom do not hunt – do not support killing cougars to benefit hunters or livestock ranchers. Even lions that enter into urban areas tend to be given the benefit of the doubt. In California, the before mentioned Proposition 117 was in fact a “citizen’s revolt” over what most people saw as being the mismanagement of cougars by California Department of Fish and Game. Wildlife agencies decry such citizen initiatives as meddling in their affairs and limiting their ability to do their job. Wildlife management, they claim, “should be left in the hand of the professionals.” Such claims, however, would carry more weight if wildlife was indeed managed professionally and scientifically. As noted earlier, politics and not science, decides most wildlife management decisions. This is especially true as it applies to the control of predators. In Arizona, for example, AGFD is headed by a governing board that is appointed by the governor of the state. The only qualification for membership on this board – other than political connections – is that the person must hold a hunting license. This pretty much precludes anyone who has a scientific background in wildlife management. Consequently, every member of the state board is a hunter, and most have tended to be ranchers as well.

I should state here that I am not anti-hunter, anti-hunting, or even anti cougar hunting. In fact, I am a hunter. I was introduced to the sport of hunting as a boy by my father and brother and have hunted all of my life. Hunting played a major role in forming the type of person I am today. It got me out of the house and into the natural world which I fell in love with. In time, the hunt, and certainly the killing, became less important as I opened my eyes and mind to the wonders that surrounded me. I became a student of the natural world and devoted myself to understanding and protecting it. I still hunt today and understand the enjoyment that comes from being outdoors and matching your skills and knowledge against the animals you seek. I have never hunted lions and don’t care to, but I don’t fault those who do. Most mountain lion hunting is done with trained hounds. As someone who has hunted behind bird dogs and rabbit hounds all of my life, I can also understand the excitement and satisfaction a cougar hunter must feel following a pack of hounds he has personally trained – hounds that were born for the hunt – hounds who can only know happiness and self-fulfillment in their own lives if they are engaged in the chase. But I admit that this is where my understanding stops. A successful lion hunt ends with the cougar “treed” or brought to bay against the rocks. Unlike most hunting, the ultimate object of a lion hunt is simply to kill and take a trophy. One source within the AGFD estimates that over one-third of the cougars killed in his state are taken through what are called “will call” hunts. In such a hunt a professional guide will have his hounds tree a cougar. Then he will telephone a hunter who only then purchases a cougar tag and comes to shoot the lion out of the tree. Often the cougar is kept treed for days until the “sportsman” arrives. Such hunts are illegal, but common in every state. I do not see the “sport” in shooting a terrified animal out of a tree. Whereas I eat the deer or pheasant I kill, lion hunters take only the head and pelt and throw away the rest of the animal. Yes, as Patricia Dorsey insisted during our panel discussion, the state of Colorado requires hunters to remove the entire carcass of the lion they have killed from the field, but they cannot legislate that the hunter actually eat the lion. In reality, the meat is almost always thrown away. I know a lot of mountain lion hunters, and I have yet to hear one of them tell me how delicious cougar meat is, or the best way to prepare it. If the lion “hunt” itself is the sport – why is the kill so important and necessary? Why is the cougar not simply allowed to go free to chase another day? There is something deeper here at play, something troubling that I do not quite comprehend. What drives mankind to consider the act of killing in itself a sport? Each year over 5000 mountain lions are killed by sport hunters in western North America – most of which are then posed and preserved for eternity in ridiculous looking rugs or mounts with snarling faces to reflect their supposed fierceness – and by implication – the hunter’s bravery. Quite possibly nearly that many cougars are also killed each year by state and federal agents, and by ranchers for the purpose of supposedly protecting livestock, or to increase the number of game animals for hunters. In contrast, as noted earlier, cougars have killed perhaps 14 humans in the past 100 years. In reflecting upon these things the question emerges: Who is the real beast in this equation? Is it the cougar that kills only for food and survival? Or is it the human that kills for enjoyment and trophies?

Wildlife agencies need to revise their protocols as to how they deal with lions that enter into urban areas. This includes using – and if need be developing – alternative non-lethal methods of capturing and relocating such cougars. As noted earlier in the Sabino Canyon situation, Harley Shaw – perhaps the nation’s foremost cougar expert and a lion biologist for 27 years with AGFD – advised trying to first haze the animals away from people. AGFD steadfastly refused trying to do so.

Wildlife management must also acknowledge the inherent rights that mountain lions – indeed all animals – possess. During our panel discussion at Fort Lewis College, Dave Baron asked each of us the question: “Should mountain lions have rights?” I was the only one who answered affirmatively.

I admit to being a spiritual person and that my spirituality has been forged from a life time of living among Native American people. I believe that the same Creative Power that made humans, also made cougars, and that we generally possess the same “natural rights.” I believe that animals’ like cougars possess basic rights that stand alone. Their rights are apart from, and independent of, the desires of humans. They possess the inherent right to live and pursue their own purpose, a purpose perhaps known only to the Creator. In other words, a cougar has the basic right to be a cougar.

In contrast, Judeo-Christian tradition – upon which western science and modern day wildlife management is based – tells us that man was created in “God’s image.” This separate and elevated creation sets the table for how we deal with other life forms. The Book of Genesis goes on to state that humankind is given “dominion over the fishes of the sea, the birds of the air, and the beasts of the earth.” In sum, all life on Earth has been placed here solely for our own use and pleasure.

The time has come to stop treating wildlife as private property.

In addition to controlling lions, we need to control people. We need, for example, to bring a halt to our encroachment into cougar country. States, counties, and cities must curb urban expansion and its consequent destruction of habitat. Any planning for growth and economic development must seriously take into account the needs of wildlife.

Everyone wants to move into those beautiful wooded valleys and canyons. Everyone wants to look outside their back window and see Bambi and Thumper contently munching on the corn, apples, and lettuce they have put out for them. But when a cougar shows up and snatches one of those cute and cuddly wild creatures, these same people scream for blood and revenge. Sadly we live in a “rights society” where we believe that it is out right as humans to live where we please and do what we please. But with rights always come responsibility. It is our responsibility as humans living in mountain lion habitat to keep our children, pets, and livestock under safe supervision and protection. It is also the right – the absolute duty – of the appropriate government we live under to pass and enforce laws that see to it that we do. If we are going to encroach on cougar habitat, it is also our absolute responsibility to take every step necessary to avoid conflict with this great predator.

In 2005, a group comprised of almost every leading mountain lion biologist in the country came together to complete a publication entitled Cougar Management Guidelines. Although there are major gaps in this work, these guidelines represent the most comprehensive, sensible, and honest set of ideas yet to be advanced on how wildlife agencies should manage and deal with mountain lions – including what can be interpreted as a suggestion to end spring cougar hunting. One of the most important contributions offered in these guidelines are research-based recommendations as to how to determine through mountain lion “body language” the risk behavior associated with various human-cougar encounters, and a suggested protocol that agencies can follow before and after such encounters take place. These guidelines offer great promise in the field of cougar management and hopefully this group will reconvene periodically to expand and update this document. In the meantime, state wildlife agencies should move to adopt these guidelines. Sadly, this does not seem to be the case in Arizona. In 2009, when AGFD released their Mountain Lion and Bear Conservation Strategies Report, it showed no evidence – other than being listed in the bibliography – that anyone in the department even read the guidelines.

5. We need to educate the general public about the beauty and wonder of mountain lions – not scare them over the potential threat that they might pose.

We fear that which we do not know or understand, and the average person knows and understands very little about mountain lions.

It was the eminent biologist Edward O. Wilson who in 1984 proposed the biophilia hypothesis – namely the idea that human beings have an innate affinity for all living things. Wilson believed that we are drawn to and want to be near other forms of life. The biophilia hypothesis explains our inherent desire to pick up and hold a warm, fuzzy puppy. It explains why we go out of our way to help an injured animal. It explains why we are so fascinated with creatures of the natural world. Perhaps the biophilia hypothesis explains why as a child I spent so much of my time out of doors roaming the fields and woodlands near my home catching snakes, turtles, frogs, and salamanders. It probably explains why as a youth I read anything and everything I could about nature and wildlife. It might also explain the many hours I spent in front of the television watching Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom, The Underwater World of Jacques Cousteau, or Walt Disney special presentations like Charlie the Lonesome Cougar.

Unfortunately, the age of biophilia seems to have given way to an era of biophobia. Today – as Richard Louv tells us so brilliantly in his book Last Child in the Woods, our young people suffer from a “nature deficit disorder.” They live in a world of computers, i-Phones, i-Pods, i-Pads, and X-boxes – all of which serve to isolate and alienate them from the natural world. Even worst, we seem to purposefully teach our young people to fear not respect nature. What most people think they know about wildlife is largely a product of the “reality television” of Animal Planet or the Discovery Channel – once proud educational networks now reduced to trash programming geared towards terrorizing people about the dangers of the natural world and wild animals – shows with provocative and sensational titles such as “When Animals Attack,” “When Animals Snap.” “Untamed and Uncut,” “Rogue Nature,” “Your Worst Animal Nightmares,” and the ever popular “Top Ten Most Shocking Animal Attacks.” All of these programs are built on a theme of animal attacks, and all have at one time or another focused on cougar attacks. If, as Marshall Macluhan once suggested, “The medium is the message,” the message that networks like Animal Planet and the Discovery Channel send out today is a distorted and poisoned one.

Wildlife agencies, parks, and other organizations legally responsible for potential animal attacks and fearing lawsuits, also tend to purposefully spread fear-based misinformation regarding the true nature of mountain lions. Every one of these groups produces and then distributes untold numbers of “educational” brochures which are designed to scare people away from lions. They exaggerate the threat from cougars, offer misleading and often false information on cougar behavior – usually “warning signs” of “aggressive” behavior – and always end with a stern message of “Report all lion sightings to the proper authority.” But as we know with the Sabino lion affair, a reported lion most often becomes a dead lion.

In closing this section, let me make two specific recommendations:

First, every state legislature should pass “no fault” legislation that provides blanket protection for state wildlife agencies from lawsuits involving animal attacks. The before-mentioned Knochel lawsuit, for example, should never have happened. Removing the threat of lawsuits will allow state wildlife agencies to view and promote mountain lions as the magnificent animals they are, and not simply as legal liabilities.

Secondly, wildlife agencies and other entities charged with educating the public need to emphasize the positive, rather than the negative, of mountain lions and mountain lion behavior. Again, most cougar education is geared toward promoting fear, not appreciation of this amazing cat. We need to turn this around. Many state wildlife agencies utilize some version of a teacher education program called Project WILD. The goal of this program is to train public school teachers so that they can incorporate wildlife education into their classroom curriculum. For many years I was a Project WILD trainer and instructor for AGFD and can testify first hand that it is a highly effective program. Project WILD (AGFD eventually renamed their version Arizona WILD) does not promote or criticize hunting. Instead it focuses primarily on natural history and ecosystems. Although the “lessons” are set and predetermined, the individual instructor is allowed a great deal of flexibility in what he or she can incorporate. While it is important that Project WILD instructors avoid politics, propaganda, and their own prejudices, the program can provide a great vehicle to promote a more comprehensive understanding of mountain lions and other predators. One thing that Project WILD can do is to direct classroom teachers to the many high quality resources and materials available to them. There is also an abundance of excellent materials readily accessible to teachers. I have listed a number of these at the end of this essay.

Closing Thoughts

“The white man looks out at the natural world, at the animals and the plants, and he sees resources. The Indian looks out at the animals and plants, and he sees relatives.”

Oren Lyons, Onondaga Nation

The positions I have staked out in this essay, and the opinions I have expressed, are a result of a life time of being outdoors and learning about wildlife, my own research on cougars, and especially the time I have spent with Native American traditionalists and intellectuals. My belief that mountain lions are spiritual creations, that they are sentient beings who are motivated by rationale thought and possess inherent rights, and that they have not been placed on this earth solely for human exploitation and convenience, is based on a set of core values long held by traditional Native American cultures. The tribal world accepts the fact that human beings are not all that special. Certainly we have no elevated status or rights above that of other life forms. We are only one of many beings caught up in an intricate web of life and death comprised of a network of reciprocal and appropriate relationships. Cooperation, not competition, makes this web of life work for all of us. It is this spirit of cooperation that I believe must form the foundation from which we can reestablish our relationship with the cougar.

The Navajos believe that when an animal appears somewhere out of place – somewhere it would normally not be found – it is bringing us a message. The mountain lions that are entering into our cities and urban areas are most certainly sending us a message. They are telling us that we must stop reducing and degrading their habitat, that we have pushed them to the brink, and that they have no where else to go. Hopefully humans will take this message to heart.

Testimonies

Mountain Lion Comments – KOFA

Comments to the Public Forum of the Sabino Canon Mountain

Mountain Lion Comments – Goat Mountain

Suggested Reading and Resource Materials

ABC Video Publishing Company (Video). 1990. Cougar: Ghost of the Rockies.

Cougar Management Guidelines Working Group. 2005. Cougar Management Guidelines. Bainbridge Island, WA: WildFutures.

David Baron. 2003. The Beast in the Garden: A Modern Parable of Man and Nature. New York: W.S. Norton & Company.

Marc Bekoff and Cara Blessley Lowe (Editors). 2007. Listening to Cougar. Boulder: University of Colorado Press.

Chris Boliano. 1995. Mountain Lion: An Unnatural History of Pumas and People. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books.

Robert H. Busch. 1996. The Cougar Almanac: A Complete Natural History of the Mountain Lion. Guilford, CT: The Lyons Press.

Cougar Management Guidelines Working Group. 2005. Cougar Management Guidelines. Bainbridge Island, WA: WildFutures.

Kevin Hansen. 1992. Cougar: The American Lion. Flagstaff, AZ: Northland Press.

Kenneth A. Logan and Linda A. Sweanor. 2001. Desert Puma: Evolutionary Ecology and Conservation of an Enduring Carnivore. Washington, D.C.: Island Press.

Richard Louv. 2008. Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder. Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin Books.

The National Geographic Society (Video). 1996. Puma: Lions of the Andes.

Elizabeth Marshall Thomas. 1994. The Tribe of the Tiger: Cats and Their Culture. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Harley Shaw. 2000. Soul Among Lions: The Cougar as Peaceful Adversary. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Other Suggested Sources of Information

Mountain Lion Foundation

P.O. Box 1896

Sacramento, CA 95812

916-442-2600

800-319-7621

www.mountainlion.org

The Cougar Fund

P.O. Box 122

Jackson, WY 83001

307-733-0797

800-248-9930

www.cougarfund.org

On March 15, 2011 it was my honor to be interviewed by Julie West of the Mountain Lion Foundation (MLF) which is based in Sacramento, California, as part of their “ON AIR” podcast series. The topic of my interview was “Native Americans and Mountain Lions.” MLF is a national nonprofit conservation and education organization dedicated to increasing understanding of, and protection for mountain lions (cougars) and their habitat. MLF is one of the oldest and most respected grassroots environmental activist groups in the nation. In 1990 they spearheaded a successful effort to pass the California Wildlife Protection Act – Proposition 117 – landmark legislation that permanently banned the sport hunting of cougars in California, restricted the depredation killing of cougars, and set aside $30 million dollars annually in state funding to acquire and protect critical habitat for all wildlife species. The passage of this law was necessitated by decades of state mismanagement of mountain lions, and reflected a true “grassroots” movement on the part of the citizens of California.

On March 15, 2011 it was my honor to be interviewed by Julie West of the Mountain Lion Foundation (MLF) which is based in Sacramento, California, as part of their “ON AIR” podcast series. The topic of my interview was “Native Americans and Mountain Lions.” MLF is a national nonprofit conservation and education organization dedicated to increasing understanding of, and protection for mountain lions (cougars) and their habitat. MLF is one of the oldest and most respected grassroots environmental activist groups in the nation. In 1990 they spearheaded a successful effort to pass the California Wildlife Protection Act – Proposition 117 – landmark legislation that permanently banned the sport hunting of cougars in California, restricted the depredation killing of cougars, and set aside $30 million dollars annually in state funding to acquire and protect critical habitat for all wildlife species. The passage of this law was necessitated by decades of state mismanagement of mountain lions, and reflected a true “grassroots” movement on the part of the citizens of California.